Marnock’s Philanthropy

Robert Marnock was one of the primary institutional gardeners to invest his time and energies into philanthropic activities for horticulture. He attended the celebratory Annual Horticulturalists and Agriculturalists dinner in January 1839 where the Gardeners’ Benevolent Institution was founded and received a special toast for his work at Sheffield. This was a friendly society offering pensions to infirm and elderly gardeners and their widows. Its charitable work for professional gardeners continues today as Perennial.

Marnock served on the original Gardeners’ Benevolent committee and between 1860-1864 he was also on its management committee, where he played a key role in considering deserving candidates for the funds and, according to the Gardeners Chronicle, ‘took a lively interest’ in its activities. Generous in his personal donations and time, he encouraged his Yorkshire contacts to provide funds to aid their own community of gardeners. He supported the application of local candidates, including John Mearns, head gardener at Welbeck Abbey. In recognition of his achievements and leadership within the trade, Marnock presided at the 35th Annual Festival Dinner of the Gardeners’ Benevolent in 1878 despite modestly saying ‘it is a duty for which I have no natural fitness’ and became a vice-president in 1882.

His philanthropy did not end with the new society. In 1845 Marnock, already an experienced horticultural journalist, was appointed editor of the new United Gardeners and Land Stewards Journal (1845-47), whose masthead nobly declared that its profits would be ‘devoted to the relief of aged and indigent gardeners and land stewards, their widows and orphans.’ For Marnock the work was not entirely altruistic, as he was paid £122 a quarter (around £8,000 today). The journal was supported by subscriptions from a consortium of around 300 professional gardeners. It featured articles and cultivation advice from these gardeners and was managed by a committee of senior nurserymen and head gardeners at major estates. Championing gardeners’ conditions and wages, Marnock declared in 1845 in the United Gardeners that ‘it is a disgrace to the nobility of Britain that their gardeners are paid no more than the labourers who perform the commonest work.’

Masthead of the United Gardeners and Land Stewards Journal, January 11, 1845. Image by permission of the British Library.

Attempts to form an association between the new journal and the established Gardeners’ Benevolent failed, which led to the first edition of United Gardeners being ‘anxious to explain’ that it believed ‘the field sufficiently wide for all’ who had ‘the same charitable object in view’.

Whether the journal’s profits did indeed reach poor gardeners’ families is questionable: it took a while to start making money and then Marnock was said to have controversially proposed that the first profits should pay for a monument in memory of his mentor and friend J. C. Loudon, an idea which drew heavy criticism.

After merging with the Gardeners Gazette and the Farmers Journal in 1847, the new Gardeners and Farmers Journal sought to remind ‘Gentlemen connected with Farming and Gardening’ that ‘by subscribing to this Journal, they are not only encouraging a work of importance to their own interests, but at the same time supporting a charity for the decayed members of two very useful and intelligent classes of servants [gardeners and farmers], when poverty overtakes them.’

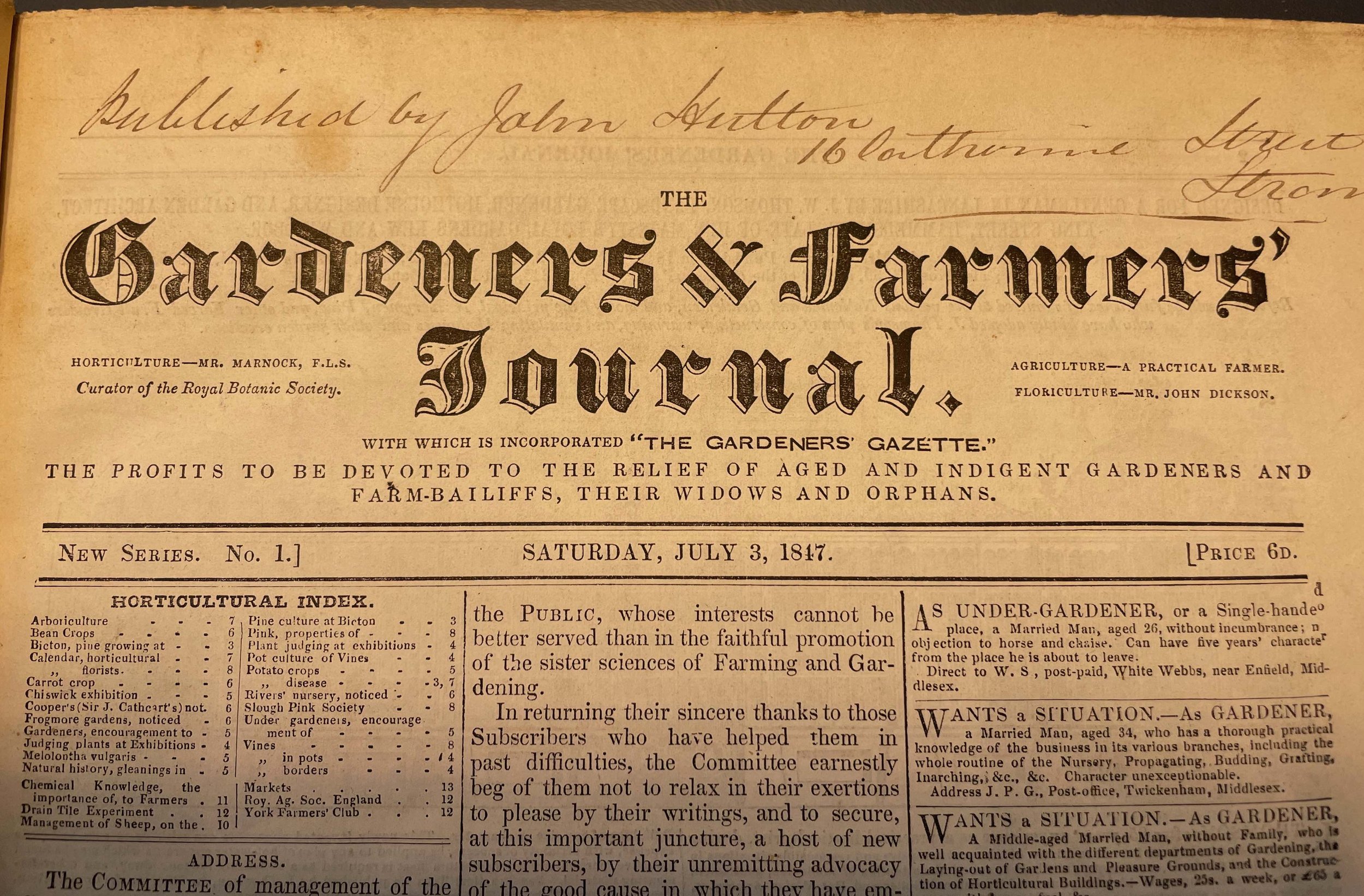

The masthead of the Gardeners & Farmers Journal, July 3, 1847. Image by permission of the British Library.

Never forgetting his roots, Marnock was appointed a director of the Scottish Gardeners’ and Land Stewards’ Association in 1850, when the altruistic masthead was dropped from the United Gardeners masthead. This association had similar charitable aims for the ‘relief of aged and infirm gardeners, land stewards and foresters and their widows and orphans’ and, being a Scottish gardener in London, Marnock could represent this large community of gardeners working in the metropolis. His philanthropic efforts towards the collective care of his fellow gardeners, and encouragement of thrift, were much praised; his obituary in the Gardeners Chronicle noted that he had secured ‘admiration for his talents and the highest esteem for his qualities as a man’.

We’re grateful to PhD scholar Francesca Murray for sharing this research with us.